'No Economy Is An Island' - but is the UK cast adrift?

Commentary by Kathleen Tyson - November 12, 2021

A paper was published in the Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin on the exposure of the UK economy to foreign shocks and market disruption: No economy is an island: how foreign shocks affect UK macrofinancial stability. It further builds the case for each central bank to understand and manage multicurrency systemic risks and dysfunction spillovers in this interconnected and vulnerable world economy.

The paper measures tremendous damaging spillovers from liquidity and market dysfunction to the British economy and financial sector. Well worth the read, but I'll summarise the highlights:

As an open economy 'highly integrated into the global trade and financial systems' events overseas can have substantial impact on the UK economy.

Monitoring foreign developments and maintaining 'safe openness' for the UK economy and financial system 'underpins the Bank of England's efforts to promote the good of the people of the UK.'

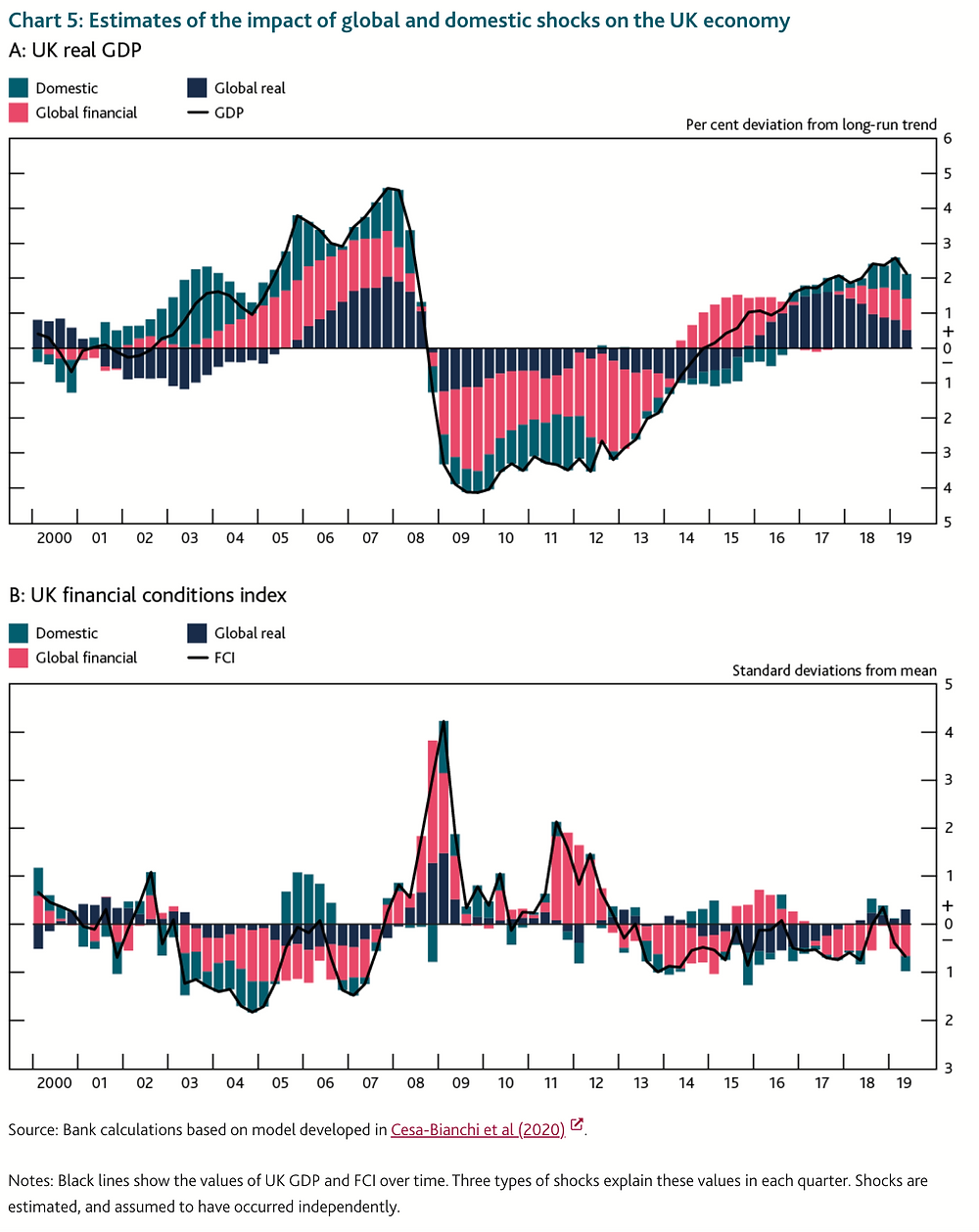

Developments abroad account for 'around half the variation in UK economic activity and almost all of the variation in a summary measure of UK financial market conditions from 1997 to 2019.'

Global developments account for over two thirds of variation in UK economic tail risk and also greater impact.

The Bank of England contributed to post-GFC reforms to support 'safe openness' and continues to work with UK and international authorities to ensure resilience to future shocks, including vulnerabilities highlighted by the pandemic.

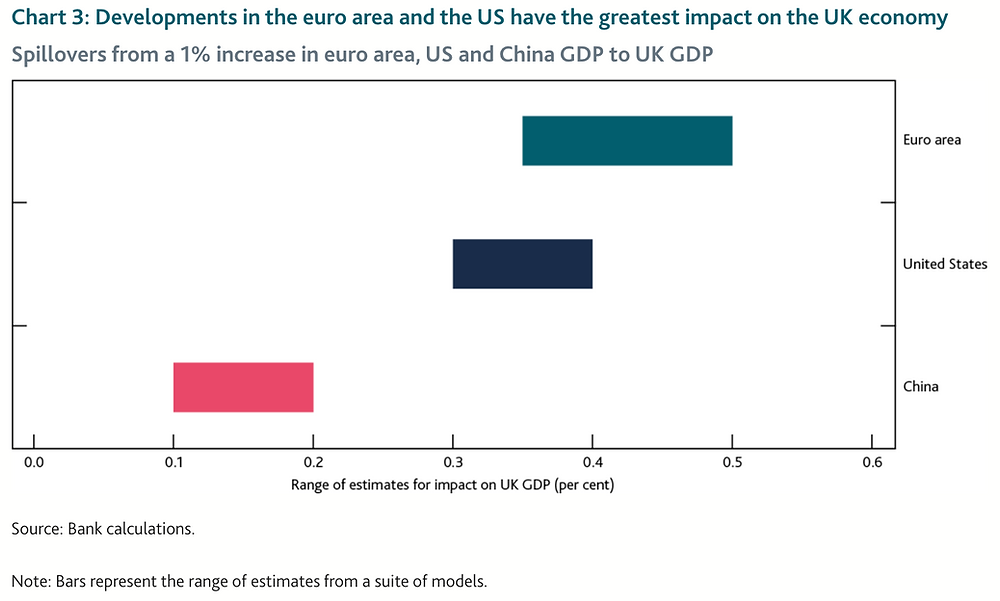

So, by this account, the actions and inactions of the Bank of England, UK Treasury, and all other UK policy makers are responsible for about half the variation in UK economic performance and financial market conditions in normal conditions and about a third in tail risk scenarios. All the rest of UK variation in performance gets imported from abroad - mostly from the US but also from the EU and, to a lesser degree, China.

The Bank of England is lucky enough to be one of the five central banks with permanent bilateral swap lines (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Bank of England, European Central Bank, Swiss National Bank, and Bank of Japan). As the UK does not have to wait for an emergency swap line - like 9 other economies severely damaged by US contagion last year - the spillovers here in the UK are much less dramatic than they are other places. And those without any swap line suffer much, much more in permanent damage from spillovers.

That's kind of scary, isn't it? No matter how wise and prudent and farsighted UK policy makers, the UK economy and financial conditions will be mostly dictated by foreign policies and events over which the UK has no control. UK influence in the US was always a matter of British wishful thinking. UK influence in the EU is now almost nonexistent post-Brexit. UK influence in China was growing and deepening until the UK was bullied by the US into dropping Huawei from UK infrastructure for 5G, picking a fight over Hong Kong, and cruising its warships in the South China Sea. As Henry Kissinger once observed, "To be America's enemy may be dangerous, but to be her friend is fatal."

The reasons that UK authorities lack command of the monetary and financial winds of change in the UK are threefold:

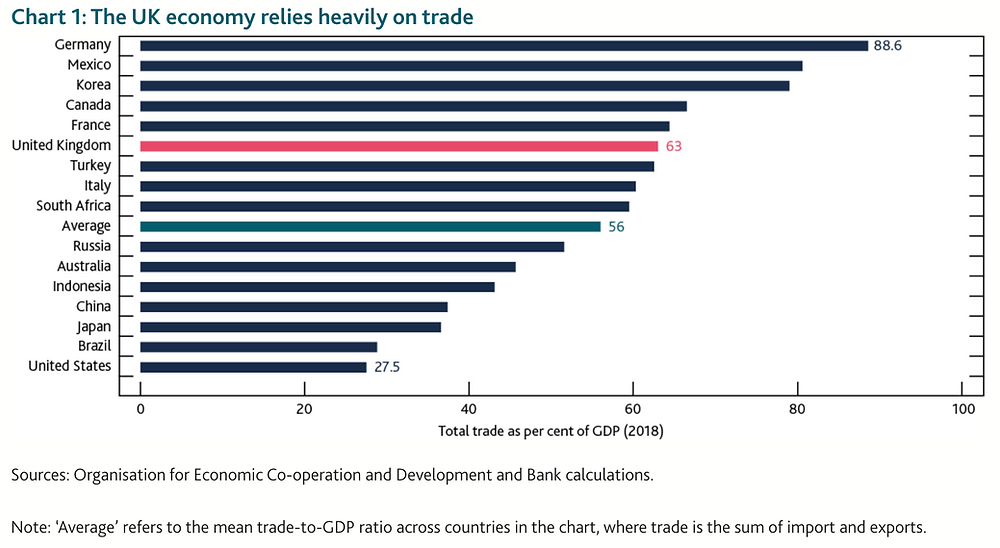

The UK economy relies heavily on trade:

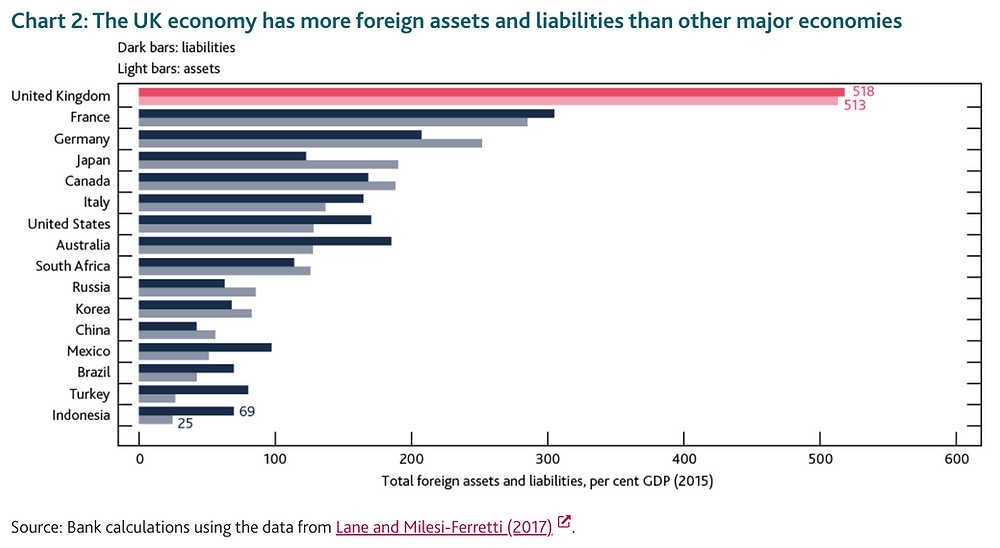

The UK economy has more foreign assets and liabilities than other major economies:

Spillovers from the US, EU and China have greater impact in the UK:

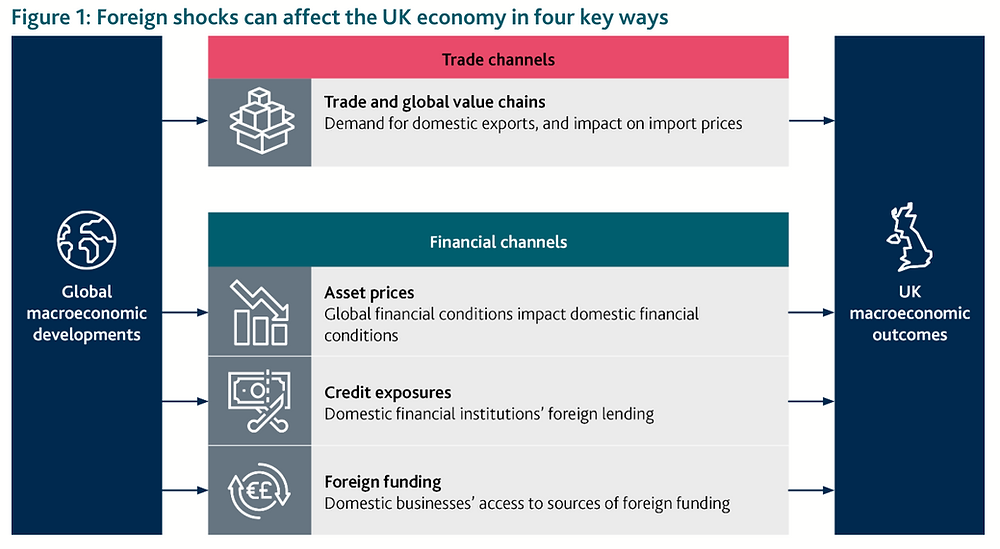

Transmission of shocks from abroad to the UK comes through in trade and supply chains (as with the current high rates of inflation due to supply chain disruptions globally), asset prices (forced selling from prime brokerage or CCP margin calls in response to foreign shocks or market dysfunction), credit exposures (as with downrating of the Chinese property sector in the past 3 months since the Evergrande difficulties first signalled a systemic credit issue), and foreign funding (as foreign investors flee Sterling or UK assets in response to global volatility or margin calls).

"On average over the 1997-2019 period, global shocks explain 52 percent of the variation in UK GDP and 90 percent of the variation in our UK financial conditions index." A global financial shock is more important than a global real shock.

This is all well and good, and we welcome the research into measuring interdependencies, but the paper does nothing to provide other central banks with models or tools for anticipating harm or mitigating harm when spillovers cross the border from foreign shocks or market dysfunction.

The desire for 'safe openness' is admirable. The lack of practical options beyond more coordination with 'international authorities' is worrying. BIS and IOSCO policies have consistently undermined liquidity, depth and capacity in global capital markets for over 20 years no matter what policy makers may have intended. More of the same doesn't make for better markets, financial stability or economic performance.

I am reminded of Riksbank Governor Stefan Ingves' December 2020 speech, Monetary policy in a changing world. Governor Ingves admitted that the central bank of a small open economy lacks the tools to fight spillovers from abroad and welcomed financial innovation to address the gaps. Here at Pacemaker.Global we took that invitation to heart and are developing the tools that Sweden, the UK, and other open economies need to anticipate and mitigate the effects of foreign spillovers as realists and pragmatists. It may not be fashionable to build better infrastructure rather than just rewrite the rulebooks, but we rather think it will make a contribution to safer and more stable world markets and economic performance.